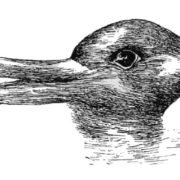

It was Wittgenstein who sparked philosophical interest in what psychologists call ambiguous figures.[1] The phrase “seeing as” became a staple of philosophical vocabulary and various uses were made of it. I want to revisit the topic in the hope of gaining some clarity on the matter. There are many instances of so-called ambiguous figures: Rubin’s vase, the Necker cube, Schroeder’s stairs, old woman/young woman, etc. What they all have in common is well illustrated by the duck-rabbit drawing, so I will focus on it. A single physical stimulus—lines drawn on paper—can appear to be a picture of a duck as well as a picture of a rabbit. I will begin by simply describing the case compendiously so that we have it as clearly in our mind as possible (I recommend having another look at it).

First, the two aspects alternate over time, now a duck, now a rabbit; they never appear at the same time—it is impossible to see both simultaneously. Second, the physical stimulus remains unchanged and is perceived to remain unchanged; we don’t perceive it to alter in any way as aspect succeeds aspect. This is a perceptual object as much as the aspects it affords—a certain fixed pattern of lines that we see as such. It is a phenomenological invariant. Third, the aspects presented are not themselves ambiguous: they are clearly either duck or rabbit, as clear as simply seeing a duck picture or a rabbit picture. Fourth, the alternation is only partially a matter the subject’s will: it typically happens automatically, though the process can be accelerated by an effort of will. The shift of perception does not emanate from any change in the stimulus and it is also not a matter of simple choice; it seems natural to say that the brain does it, an agency unto itself. Fifth, there is no reason to suppose that the stimulus is incapable of being seen in only one way: it is perfectly conceivable that some perceivers will see it only as a duck and some only as a rabbit—say, if they had knowledge of only one kind of animal. The very same stimulus array would be, for these perceivers, simply a picture of a duck or a picture of a rabbit—while for us it is a picture of both. Sixth, it is noteworthy that the ambiguity is invariably binary: there are just two possible aspects associated with the stimulus in question. This seems entirely contingent: why not three aspects or even seventeen? Some possible perceivers might increase the cardinality considerably. Seventh, there is both what Wittgenstein called the dawning of an aspect, often experienced as wondrous or surprising, and then there is the steady perception of the aspect for some extended period of time, typically a few seconds. Eighth, specific parts of the stimulus are experienced as different parts of the animal depicted—the same lines are seen now as ears and now as a beak. There is part seeing-as and whole seeing-as, the latter dependent on the former. Ninth, it is not possible to produce an imaginary array that admits of this kind of ambiguity: a mental image will either be a duck picture or a rabbit picture, with no alternation between them. So the ambiguity (but see below) is a feature of the visual sense not of the visual imagination. Tenth, the effect is not confined to pictures: we can contrive cases of a stimulus in the wild that can be seen in either way. I am not aware of any experimentalist actually doing this, but it seems easy enough to envisage presenting a three-dimensional stimulus at a suitable distance from the perceiver that similarly underdetermines the type of animal seen yonder—it might elicit the same kind of alternation that a drawn picture does. Is that a duck or a rabbit in the bushes? Now it looks like a duck, now like a rabbit.

Those, I take it, are the main phenomenological facts. Now there is the question of how to interpret them, classify them, and fit them into a theory. Are they a special case of some more general phenomenon? Do they show that there is more than one type of seeing? What concepts best characterize such perception? I think most of what philosophers have had to say about these cases is wrong, ironically because of a need to overgeneralize (Wittgenstein’s bête noir). First, there is the persistent tendency to describe them in terms of ambiguity, as if this is just like linguistic ambiguity—as with the use of the phrase “ambiguous figures”. Words can be ambiguous, and visual arrays can be too: thus they belong together conceptually. But this is wrong for a number of reasons. The ambiguity of language stems from the conventional character of the relation between sound and meaning: the word “bank” can conventionally mean either money bank or riverbank. But the visual array that gives rise to the duck-rabbit effect is not conventionally related to the type of animal seen—that is really what ducks and rabbits look like. What we have here is under-determination not ambiguity: there is nothing arbitrary about the relation between the array and the animals depicted—it is simply consistent with both. Also, there is no phenomenon of meaning alternation with ambiguous words: it is not that if you stare at the word “bank” or hear it uttered many times your perception of its meaning changes, now meaning money bank and now meaning riverbank. Nor is it true that the shift of aspect is a shift of meaning: we don’t perceive the array as a symbol that can mean one thing or another—we perceive it as a picture of one thing or another. Nor, further, is there any question of intended meaning, since the stimulus is not a linguistic act. At best it is a metaphor to speak of ambiguity here, and a misleading metaphor at that. This is a point specifically about visual perception not about language or symbolism generally. It is thus quite wrong to assimilate the duck-rabbit case to that of “bank” and the like.

Second, calling the phenomenon in question “noticing an aspect” (as Wittgenstein does) does not do it justice, since that phrase applies far more widely. We are always noticing aspects of things on the basis of perception, but we are not often subject to a duck-rabbit type of case. I may notice an aspect of your face, say the shape of your nose, but this is not an ambiguous (sic) figure case. What is crucial in such a case (as Wittgenstein himself stresses) is that we have a core of perception that does not change under a change of aspect, corresponding to the physical stimulus. But merely noticing an aspect does not involve anything like that; generally speaking, it involves noticing precisely an intrinsic feature of the stimulus (say, the way your nose physically curves). I would prefer to call duck-rabbit cases “alternating aspect” cases, not “noticing an aspect” cases (or “ambiguous figure” cases). The same goes for the phrase “seeing as”: that phrase applies to all seeing not just to what happens in a duck-rabbit case. I see you as tall, my cat as speckled, my car as shiny: that is, I see things as having properties. But that doesn’t capture what is distinctive about duck-rabbit cases, as I described them above—particularly, the constancy of the visual core and the unwilled alternation of the aspects. Granted, it is difficult to describe the phenomenon concisely in a single phrase, but these standard descriptions are positively misleading (and have misled). I think the phrases “imaginative seeing” or “interpretative seeing” invite similar objections, since they too apply more widely, but I won’t labor the point further.

A more interesting question is whether the apparatus of sense and reference applies here. On the face of it, it does: two modes of presentation associated with a common object. The same patch of lines can give rise to two ways of seeing it, as the same planet can be perceived in two ways corresponding to “the evening star” and “the morning star”. Why not say that the common object corresponds to two “senses”, a duck sense and a rabbit sense? Couldn’t someone see the patch as a duck in one context and a rabbit in another, and then come to realize that it is the same patch that is involved? Isn’t the structure much the same in alternating aspects cases and sense-reference cases? And didn’t Frege himself characterize modes of presentation as “aspects”? It turns out that his apparatus applies more widely than he thought: the duck-rabbit drawing is a special case of sense and reference. That is certainly a pleasant conjecture, but it is flawed at a crucial point, namely that the common element is actually perceived in the duck-rabbit case, i.e. it occurs as a phenomenological datum. We see the duck, the rabbit, and the lines; but in the case of sense and reference we don’t have a separate presentation of the reference aside from its two modes of presentation. We are not seeing the same physical stimulus, perceptually represented as such, giving rise to two aspects in the case of the evening star and the morning star, as we are in the duck-rabbit case. Nor, of course, do we oscillate from one sense to the other while gazing intently at Venus. So the structure isn’t the same in the two cases despite a superficial resemblance. The perceived unchanging core is not present in Frege-type cases, so the one is not a special case of the other.

It seems to me that alternating aspect cases are genuinely sui generis. There is really nothing like them, which is why a general label is elusive (like “ambiguous figure” or “noticing an aspect” or “seeing as”). But it doesn’t follow that they involve a special type of seeing, as opposed to a unique type of perceptual phenomenon. On the contrary, it seems to me that the same type of seeing is involved here as elsewhere. Suppose you see a picture of a duck but without any alternation with a picture of a rabbit. This could be exactly like the experience you have when looking at a duck-rabbit picture and see its duck aspect: the experience is not altered by being caused by an “ambiguous figure”. No new type of seeing is occasioned by such figures in addition to the experiences occasioned by unambiguous duck pictures. Similarly, if an experimenter could contrive a stimulus that could be perceived as a duck or as a rabbit (not as a picture of such), that would not cause any experiences additional to those caused by ducks and rabbits. The possibility of alternation doesn’t alter the nature of the experience had when seeing a single aspect. So the duck-rabbit case and others like it don’t require us to expand our phenomenological inventory beyond the seeing of ducks and rabbits (or pictures of them). Indeed, we might well claim that all seeing is seeing-as (an object as having a property) and that the duck-rabbit cases add nothing to this simple picture. They merely show that there can be alternations of aspect under conditions of stimulus identity.

It is sometimes supposed that the kind of seeing that goes on in duck-rabbit cases is relevant to pictorial perception: this kind of perception is supposed to differ from object perception and to be a special case of seeing-as, as that notion is illustrated by duck-rabbit cases. But this idea is confused: the seeing of an aspect is the same whether there is alternation or not, so these cases cannot provide a new type of seeing. Also, the essential feature of such cases is conspicuously missing in pictorial perception, namely the alternation of aspects. Normally a painting depicts a single aspect; it isn’t “ambiguous”. Trivially, seeing a picture is a case of seeing-as because all seeing is seeing-as; but the kind of seeing-as that occurs in duck-rabbit cases is nothing special, so nothing new can be learned from it about pictorial perception. The concept of seeing-as, as philosophers have come to employ it, should really be retired or else explicitly extended to all types of seeing.

Duck-rabbit cases are highly unusual, indeed carefully contrived: they are not instances of something more general, and they shed no light on anything beyond themselves. It is surprising they exist at all, being an anomaly of the human visual system (I don’t know of any experiments that have shown other animals capable of such strange oscillations). They only occur under very special and manufactured conditions (the duck-rabbit drawing was first introduced in a German humor magazine in 1892). They appear to have no analogue in other sense modalities: there is no such case for smelling, tasting, touching or hearing. We would be in no way worse off without them; they appear to have no use except as entertainment. Contrary to Wittgenstein’s advocacy, they have no philosophical significance, except perhaps to illustrate how very peculiar things can be. Their significance is their insignificance, their sheer quirkiness.[2]

[1]See Philosophical Investigations, pp.193-208.

[2] It used to be suggested by psychologists that duck-rabbit cases are to be explained by invoking the idea of hypothesis formation: the visual system constructs a hypothesis on the basis of exiguous data and this hypothesis corresponds to a visual aspect. However, this doesn’t explain the oscillation characteristic of these cases: why does the visual system switch from one hypothesis to another for no apparent reason? That is not what scientists do when they propose a hypothesis. So this attempt to subsume the cases under the wider category of hypothesis formation also fails. As far as I know, the phenomenon has still not been satisfactorily explained.